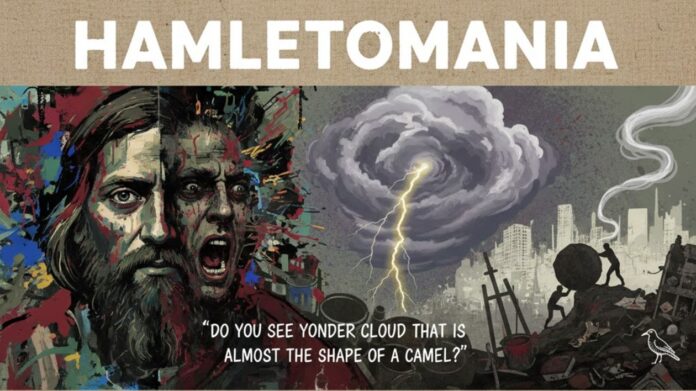

“Do you see yonder cloud that is almost the shape of a camel?”

Jørgen Nash, a Danish artist and writer, revealed this to be a remarkable question in the world of art. According to him, this simple question has inspired the artworks in Europe till now. He elaborated that there is a monstrous power that thrives within it. The kind of power that destroys individuality, all shape and code. This is both god and devil, a bolt of lightning that helps to realise the dark side. This is a struggle between two contrasting elements, Apollonian and Dionysian. These are two conflicting forces. One symbolises harmony, form, and understanding, and the other one is a symbol of excess, ugliness, and intoxication.

At that time, the Dionysian epidemic was in full blast all over the art world. But opposite to this was the success of Apollonian Hamletomania, an intelligence which seeks to moderate the storm. This war is perpetual. Similar to Sisyphus, the artist takes the rock up the hill knowing that it will roll back. And yet it is this revival that keeps art alive.

In the early 1960s, Nash travelled to London to immerse himself in English art and gather ideas for his book. But what he experienced completely astonished him. He saw a style of art that is cautious, extremely so. It lacked bold concepts or any sense of risk. Once, English poetry was powerful and fearless. But what he saw was broken and silent. Only institutional voices remained, protected and covered. The wild energy within it was not there anymore.

From the Scandinavian viewpoint, European art appeared weary. However, a handful of giants and rebels remained: Dubuffet, Jorn, and Carl-Henning Pedersen. Next, the American Revolution emerged with an essential viewpoint. When Nash observed Jackson Pollock’s paintings, certain aspects became clear to him. He felt the glorified return of actions on the canvas, along with the conflict and risk. The Cobra movement and Helhesten before it maintained this primitive, Dionysian aspect that was missing in European art. The majority of English artists did not grasp this. Gordon Fazakerley, however, did not miss.

Nash remembered that watching Fazakerley’s art felt like witnessing a battle. His method with a canvas was far from gentle, rather forceful. The brush hit quickly and forcefully. His movements seemed to follow a rough rhythm. At times, the battle concluded swiftly; other times, it lasted for several days. The studio looked like a war zone, reminiscent of Stalingrad or Guernica. Paint tubes were all around, similar to shell pieces. Cigarette smoke twists in the studio like an injured creature. Everything was dirty, everything at risk.

After his exile from England, he changed his ways. Working with Situationists from Scandinavia contributed to his development. Action, rather than his theories, influenced his poems, drawings, and paintings. Moreover, he refused to participate in non-risky optimal modern activities. He did not think ahead like a tactical chess player; he faced conflicts head-on.

Fazakerley, as a painter and a poet, refused the illusions of romance. To him, poetry is not a dream, but rather an act. Poetry happens in the context of misunderstandings. Language collapses under the weight of the forces to which it submits and takes various forms. He eagerly devoured all of these ideas.

Jørgen Nash mourned that English art in the new era seemed to be fearful. English art offers itself as a copy and remains as background. Fazakerley, however, did not remain in the background. He was not hungry for power and privilege. His Hamletomania rested on his experiences in war and the melodies of birds.

It gave Nash hope that, like Sisyphus, the struggle that gives art its meaning will never die.