What we mean by ‘emergency’ is supposed to be a specific thing. However, those in power constantly redefined the concept of ‘public enemy’, calling it an emergency. It is within the framework of an emergency that citizens learn to embrace the loss of rights. In fact, they learn to embrace it in the name of democracy. Over time, emergencies start to feel normal. The rare situations of emergencies become routine.

The impact is clear if you look at the example of Italy. Since the 1970s, the state has ruled through one emergency after another. This created a flexible but powerful system. It uses words, laws, and moral pressure to make unconstitutional actions feel normal. Emergency does not just excuse force after it happens. It reshapes law, work, and daily life in advance. Its real goal is control. It disciplines workers to block resistance. It manages anyone who steps out of line. Even fights within the ruling class follow this logic.

The first large-scale state of emergency in Italy was the so-called “war on terrorism.” The state launched it to crush the mass worker struggles of the Hot Autumn. Conflicts of a political nature became a criminal issue. The police and the judiciary substituted discussion and struggle. The state eliminated the opposition of the rebel workers. However, the struggle came to an end, but the state of emergency did not. The power of the state did not only reside in the issue of public order. It extended into relations, private life, and into the thoughts and feelings of the people.

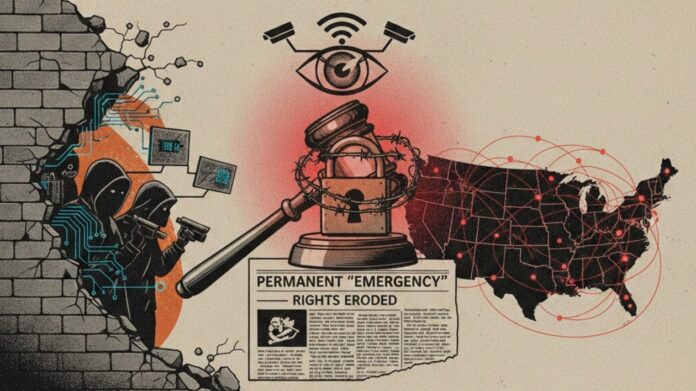

Three factors propelled the movement to the forefront. Firstly, the judiciary underwent a change. Normal laws became personalised. Punishment depended on collaboration and confession. Secondly, the media spread fear. Endless warnings sparked demands for “law and order.” Thirdly, technology was usurped by power. Surveillance spread everywhere. Cameras, wire taps, satellites, and computer tracking entered mainstream life. Italy, as before, led the way. Soon, the entire European continent followed suit.

The situation reflected the need for modern capitalism. Modern work requires less machine power and more brain power. It requires knowledge, communication, and collaboration. To control this kind of labour, power must control people from the inside. It is in this scenario that the internet becomes the ideal target. The internet enables people to network without asking permission. It upsets the established order.

At the same time, the postmodern state presented itself as neutral. It declared itself complete and absolute. It no longer asks for legitimacy through struggle. Work lost its political meaning, and labour was stripped of its creative power. Its result was merely the state of police science: prevention, control, and punishment. Emergency was no longer an interruption in the constitutional order. It became the order.

This article explored how emergency changes shape, from conflict to minute-scale domination. The rule of law, media, and technology collaborate in this transformation. We do not idealise civil liberties as we know their limitations. However, we continue to deploy them to counter power. Civil rights, which once came from struggle, became self-contradictory. The state can cite them when it is convenient to do so and defy them when it requires forced action.

“Enemies of the State” is not an impartial history. It examines how the emergency becomes a method of rule. It illustrates the process of living labour becoming a perpetual suspect. It discloses how resistance survives no matter how fragile it is. Because resistance can not vanish, no matter what era it is.