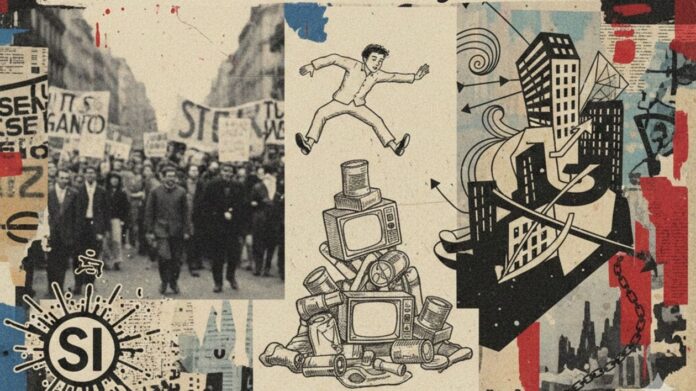

There was no avant-garde in 1960s Europe as radical as the Situationists in the Second Situationist International. They began early and acted boldly. They represented many voices. The value they created does not lie in their prophecies about the future. The value lies in their creation of the future. They launched the youth rebellion. They marked the beginning of a new creative space that we still have not discovered fully yet.

Even before Provo existed, the Situationists were already living the spirit of Provo. Simon Vinkenoog and Jacques Landsmann identified the roots of Provo among former Situationists like Constant Nieuwenhuys and Jean-Louis Brau. “Provo” was a result of Situationist ideas and sometimes from Situationists expelled from their movement. There is a clear distinction here. Humor, street behavior, urban games, direct action, everything comes from the Situationists.

Since 1961, the Second Situationist International has challenged consumer society. The Second Situationists criticized conventional art organizations. The Second Situationists protested against cold and functional urban planning. This led to police interventions resulting in fines, trials, and repression. The SPUR affair, Little Mermaid, occupation, and seizure of Copenhagen Street power protest acts were not symbols. They occurred. They influenced everyday life.

The Situationists also tore down the wall between artist and audience. In experiments like CO-RITUS, anyone was a creator. They believed in the creation together, in living the experiment. They rejected the American-style art spectacle of the 1960s. Refused was pop art, staged happenings, and official events-participation, laughter, and disruption.

No other avant-garde group of that time worked across so many countries. The Situationists acted in Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Italy, and France. They held fourteen international conferences. They published more than fifteen major books through their own press. They ran five avant-garde film festivals. They printed hundreds of pamphlets and catalogues. They made posters, films, magazines, and street actions. At the heart of it all stood the Situationist Bauhaus at Drakabygget in southern Sweden. This was a living lab where people came to work, argue, and create together.

Drakabygget greeted groups from Germany, Mexico, the United States, Italy, Denmark, Sweden, and many other places. Artists, writers, and activists mixed freely. The openness marked off the Second Situationist International from the group based in Paris around Guy Debord. That one focused on theoretical purity and control. The Second International chose to work with action, decentralisation, and open participation. Anybody could do the Situationist work. What mattered was what you did, not who you obeyed.

Because of this difference, the split came in 1962. Debord advocated exclusion and theory. The Second Situationist International advocated action, humor, and loose collaboration. In Italy, they contributed to an opposition to the Venice Biennale. They brought workers, students, and artists together. They contributed to the student movement and the emergence of Kommune 1 in Germany, where they worked on SPUR. Also, they contributed to the practices of May ’68 in France, even if this is overshadowed now by nationalist narratives.

But their actual legacy transcends dates and records of firsts. They transposed creativity into a form of social experiment. They represented a kind of anarchist power that derives from the non-political world. By means of sabotaging the media, the street, and communal rituals, they made art something that one lives. This book, through its documentation, reprinted, tells this tale. It retains the spirit. And even now, these acts continue to speak eloquently.